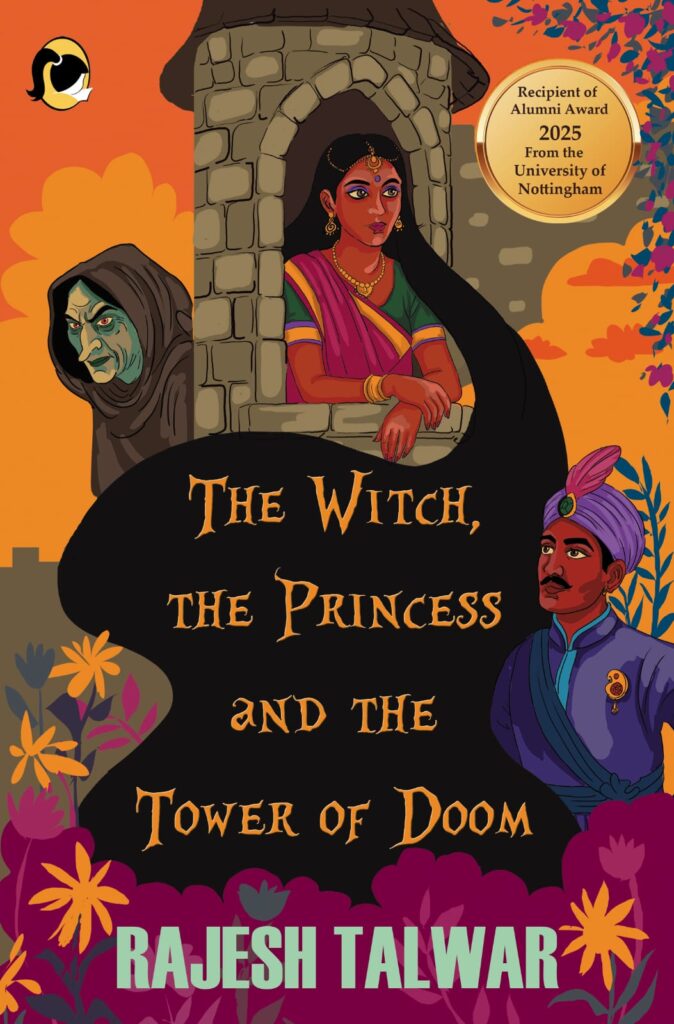

Breaking Stereotypes in Fairy Tales: A Conversation with Rajesh Talwar

In this engaging session of Talk Time with Samata, I had the pleasure of speaking with acclaimed author Rajesh Talwar, whose latest work The Witch, The Princess and The Tower of Doom reimagines the classic tale of Rapunzel through a vibrant Indian lens. With a distinguished background in law, human rights, and an illustrious career with the United Nations, Talwar brings a unique depth to children’s literature—

infusing timeless fairy tales with contemporary values, social critique, and a strong moral compass. In our conversation, he shares insights on breaking stereotypes, the inspiration behind Princess Pihu, and how fantasy can mirror real-world challenges while sparking the imagination of young readers.

Welcome Back to this session of Talk Time with Samata. How are you Sir (Rajesh Talwar) and how is your journey in the writing world going?

Its always a pleasure to be back with you. I am well and the writing journey also continues. Both are, in a way, connected to each other (smile). This year, my alma mater, the University of Nottingham was kind enough to honour me with an International Alumni Award. What made it even more special was the fact that the jury made special mention of a few of my books. If you have interest you could check them out at the university’s award link below, where I feature at the bottom of the page.

https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/alumni/community/your-nottingham-alumni-awards.aspx

Your book reimagines the Western classic Rapunzel through an Indian cultural lens. What inspired you to adapt this tale, and how did you decide on the unique character of Princess Pihu?

You know, if you stop to think of it, the Rapunzel story has a special resonance with India. I say this because Indians in general have much better-quality hair than elsewhere in the world. As a matter of fact, India is currently one of the largest exporters of human hair in the world. Many countries import hair from India, including China. Moreover, we continue to have a tradition where our girls grow their hair long, much more so than in the West. In that sense, the Rapunzel story is no longer as real or relevant in the West where the culture of having long hair is now obsolete. Anyhow, I thought it would make for a nice change to have a princess with long, black, silky hair rather than the usual golden hair and blue eyes, common in princess stories based in the West. Not that those depictions are not lovely. Just good to have a variation, you understand.

Princess Pihu breaks away from the stereotypical “damsel in distress.” Was it important for you to consciously challenge gender norms in children’s literature?

Yes, it was. I imagine that my book will be read by many young girls and I would certainly not wish to reinforce any rigid gender stereotypes. Girls too surely have a right to dream and fly, and do whatever it is that they wish to do. At the same time, I wished to avoid too much of ‘wokeism’ where sometimes a girl’s caring and sensitive side is not sufficiently valued. I should add here that Princess Pihu while gentle is also a strong and determined character in the story.

The story blends ancient Indian settings with values that feel very contemporary—such as environmental preservation and healthcare. How did you strike the balance between a timeless fairy tale and modern-day relevance?

As an author writing for children, I considered how a story reimagining a premise, that of a princess with very long hair, in our times would be enriched and be more engaging if I blended in important issues that concern all of us. And the environment and healthcare are such important issues, that it would be a shame not to have seized that opportunity.

The witch, Churailamma, is portrayed as more than just a one-dimensional villain. Without giving away spoilers, why was it important to explore her complexity?

We live in a complex world, and nowadays children also understand that. The other problem with a one-dimensional character is that it makes a story too predictable and therefore uninteresting. If I had ended the story simply with a rescue, as often happens in the conventionally told tales, it would have left the modern reader disappointed. ‘Oh, I already knew that this would happen!’ the child reader would have told himself. Stories must have several unpredictable elements and twists and turns in them for them to hold the interest of the reader. There needed to be a twist concerning the witch’s tale as well.

Your prince is not the typical heroic rescuer but someone with his own vulnerabilities. What message were you hoping young readers would take from his character?

Interestingly enough, for many readers, including both female and male ones, the prince was the most endearing character in the entire story. A hero who doesn’t have any vulnerabilities tends to be less human, and therefore less relatable. Also, less interesting. What engages a reader are situations where characters face problems, but then wage a battle externally but also within themselves to try and overcome those problems.

In the book, there’s a subtle thread of social critique—touching upon racism, caste discrimination, and the idea of inner strength over outward beauty. How do you weave such profound ideas into a children’s story without making it feel heavy-handed?

Thank you for that comment. I suppose that my travels around the world, while working for the United Nations, have indirectly influenced and informed the tale. As you know I have worked in many conflict zones such as Afghanistan, Kosovo and Somalia. In all these places, there has been conflict between different groups and ethnicities and issues of discrimination and prejudice have therefore arisen. Not to say that such issues of racism, skin colour, and discrimination in general, don’t affect so-called developed nations.

The Tower of Doom sounds both magical and symbolic. Did you intend it as a metaphor for certain real-life challenges, or is it purely part of the fantasy world?

It was intended to be a metaphor as well. I’m glad you picked up on that. All of us face challenges in life just as were faced by the princess and the prince in this tale. Sometimes in life we feel as if there is no escape from our personal ‘tower of doom,’ but with perseverance and courage we can manage to overcome our problems.

Your earlier works, like The Boy Who Wrote a Constitution, also challenge stereotypes and highlight social justice issues. How does your background in law and human rights influence your storytelling for children?

That book was indeed very special just like this one. It was so ironic and at the same time befitting that someone like Babasaheb Ambedkar who faced discrimination in his childhood as well as his adult life should have been called upon to chair the drafting of the Indian Constitution. This is the seminal document that protects the rights of the weak, the discriminated and the oppressed in our country, and Mr BR Ambedkar knew about all these issues from personal experience. Given my background in human rights and law, I simply had to write that book. Incidentally, it was so well received that a translation in Hindi should be out in the next couple of months. Hopefully there will be translations in other languages as well.

You’ve worked extensively with the UN and written across genres. How does writing a children’s fairy tale differ from writing legal critique or plays on social issues?

It is very different but we should all do different things, should we not? In earlier centuries, you had talented people who could do many different things. A person could work as a painter but also as a scientist and inventor. Leonardo da Vinci, to take only one such example. As we entered an era of specialisation, increasingly people tended to stay within set categories. Even writers began to specialise. Children’s authors were different from romance novelists who were different from writers of serious non-fiction. To my mind these are all artificial boundaries, and an artist, especially a writer, ought to try and stretch himself. In the field of music, I love Asha Bhosle for this reason. What cannot she sing? She has sung pop music, ghazals, bhajans, sad songs, peppy numbers and so on and forth. She’s even sung in Russian and Polish apart from multiple Indian languages. Music directors tried to pigeon hole her over the years but she wouldn’t let them do that.

The book has supernatural elements, but it also seems to have a strong moral compass. Do you see yourself as trying to teach values, or simply telling a story that naturally carries them?

Definitely the latter. If as a writer for children you try too hard to instil values in children your writing will come across as didactic and not flow naturally. Children don’t want to be necessarily reminded of their teachers while reading a book. Reading should be for pleasure and authors of children’s books need to take care to slip in moral values unobtrusively.

In your version of the tale, “rescue” is not a one-way act—it’s mutual between the prince and the princess. How does this dynamic reflect the kind of relationships you believe children should see in stories?

That’s a great question. While the conventional fairy tales held a great deal of charm, in a way the damsel in distress story line robbed female protagonists of their autonomy. They just had to sit back and wait to be rescued. That would have affected the self-image of female readers negatively as well. At the same time, those stories placed an impossible burden on the male protagonist, who was to be ‘perfectly’ capable, never needing any help or assistance. We need to move away from those artificial stereotypes in our storytelling.

Finally, if readers could take away just one lesson from The Witch, The Princess and The Tower of Doom, what would you want it to be?

Leave a Reply